The Estuary is not just an amazing place for animals, it’s a great place for plants, too. Below you’ll see a selection of native species you could spot at the estuary, as well as some invasive visitors that have overstayed their welcome.

Native Species

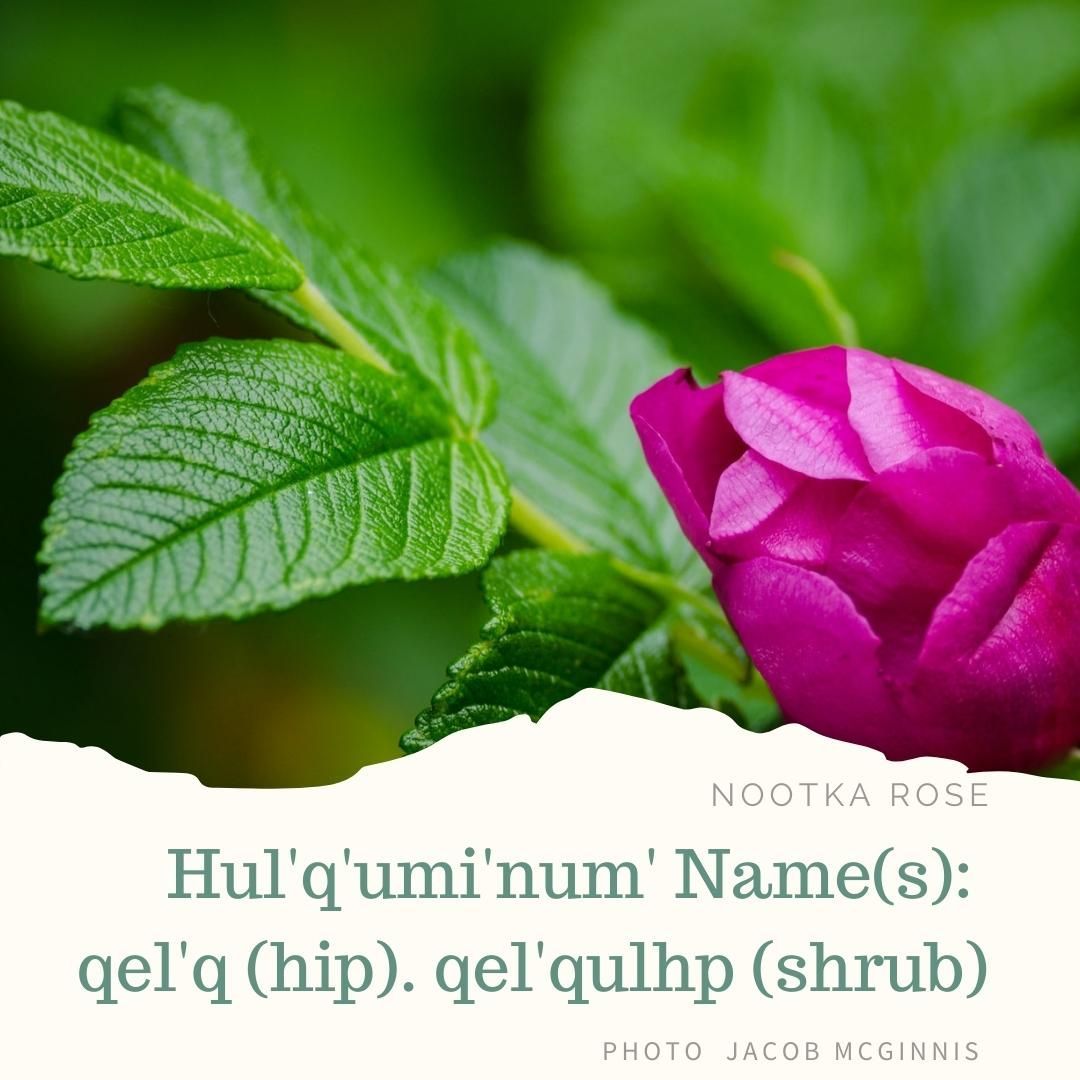

We love Nootka Rose! How about you? It’s a common native rose species found within the Cowichan Watershed and its ability to stabilize the banks of streams, rivers, and coastline makes it a helpful species for our restoration work! Did you know the Nootka Rose gets its name from the Nootka sound and the Nuu-Chah-Nulth tribe that live in the area located on the west coast of Vancouver Island?

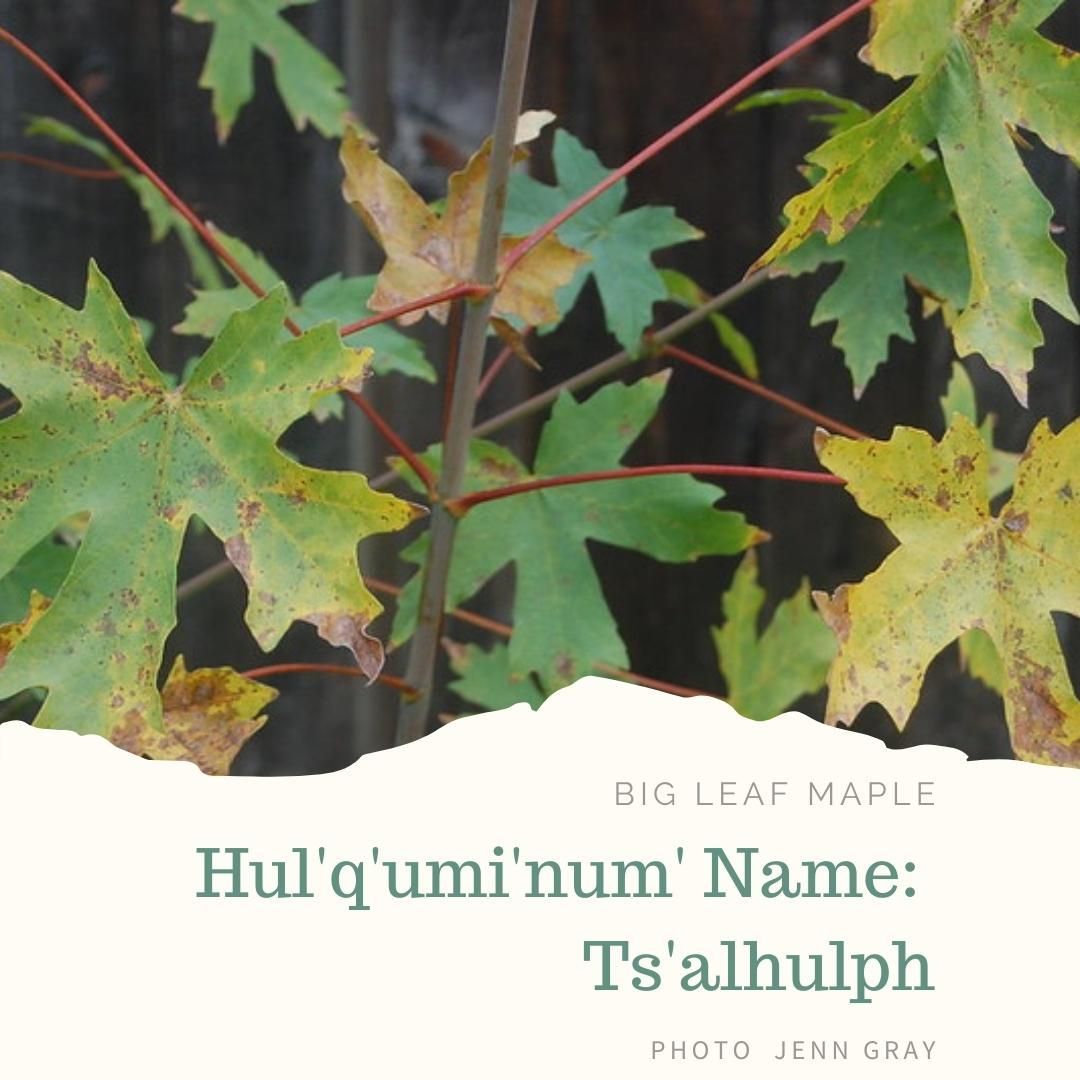

This species can have leaves up to 12-inches across which is just one of the reasons we love Big Leaf Maples! This impressive tree species has ridged bark that creates ideal habitat for epiphytes (plants that grow on trees without soil) including mosses and lichens. Birds and small mammals also love Big-Leaf Maples for their nourishing seeds, buds and flowers!

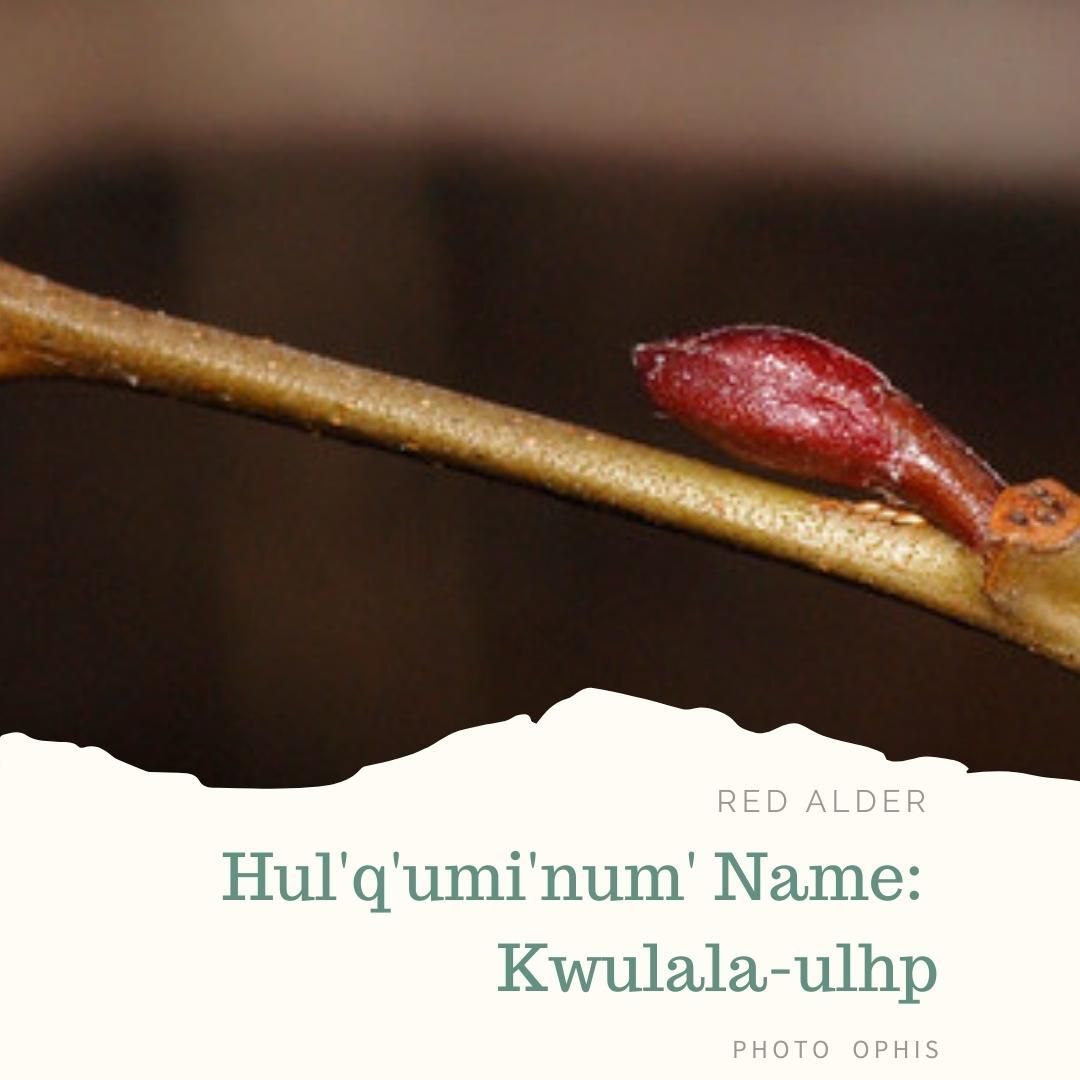

We love this fast-growing native tree species for its role in nitrogen fixing for healthy soils. Red Alder is the tree of choice in ecological restoration projects as it kick-starts natural environmental succession!

Sword Ferns love damp, shaded areas of the forest floor which makes them perfectly suited for our wet coastal climate. They’re also a beautiful native species to add to your garden!

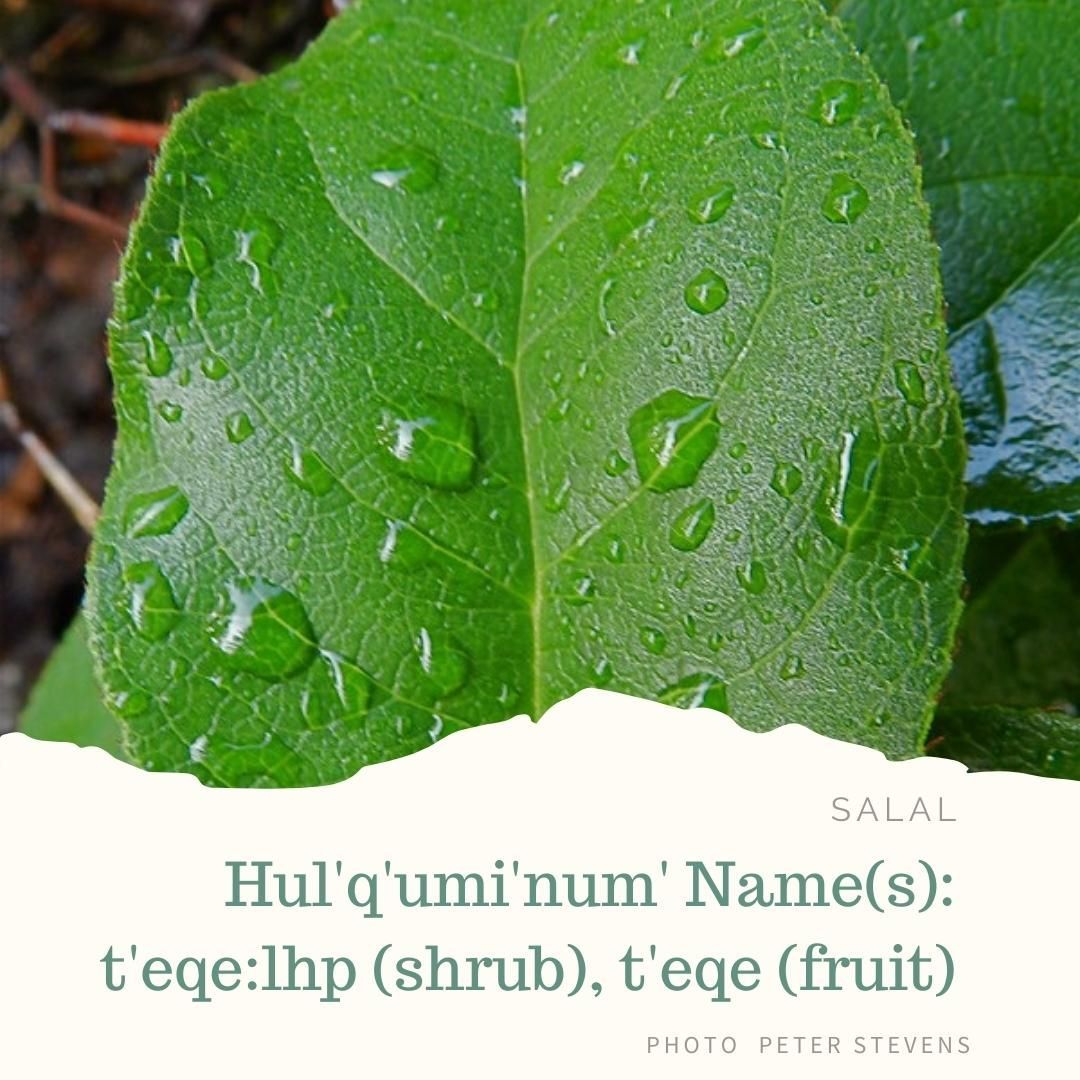

Have you ever tasted a Salal berry? We love them! In fact, we love the whole plant! Salal is a versatile native species that is found in almost all of our local landscapes. It is a favourite food for deer, squirrels, and local birds!

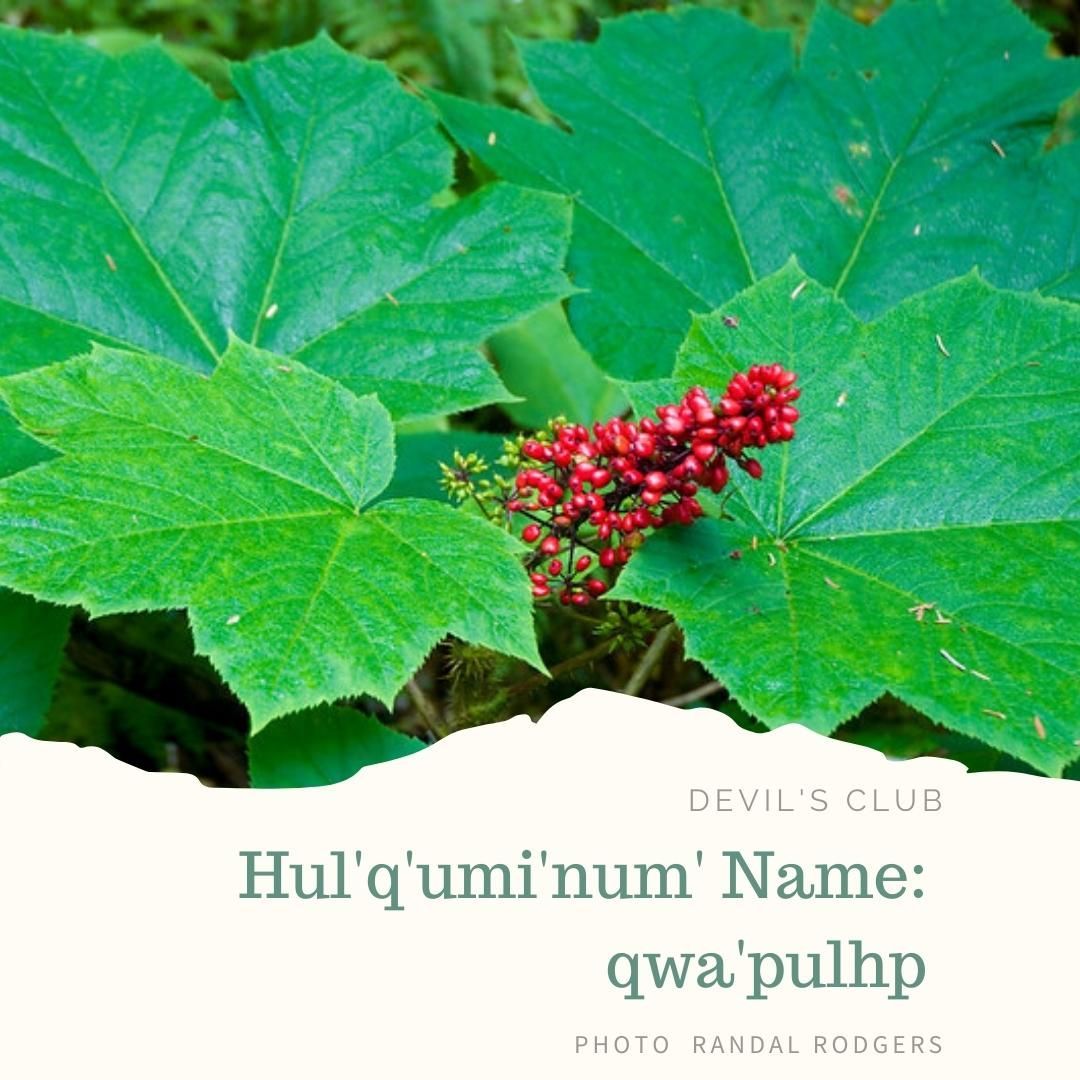

Devil’s Club is a native deciduous shrub that grows in almost all areas of British Columbia. It lives up to its name with stems and leaves that are covered in spines, and although its berries are not edible to humans, they provide important food for animals. Did you know that Parks officials in Alaska have used Devil’s Club to build a natural fence to deter park visitors from straying from the designated path? Talk about innovative thinking!

Invasive Species

Do you have English Ivy growing in your yard? It has often been planted near buildings to provide quick-growing greenery to walls and gardens but unfortunately at the expense of native species! Once established, it forms a dense ground cover that can survive without much water or sunlight, making it very difficult to get rid of. Sorry English Ivy, you may be beautiful, but our advice is: it’s got to go!

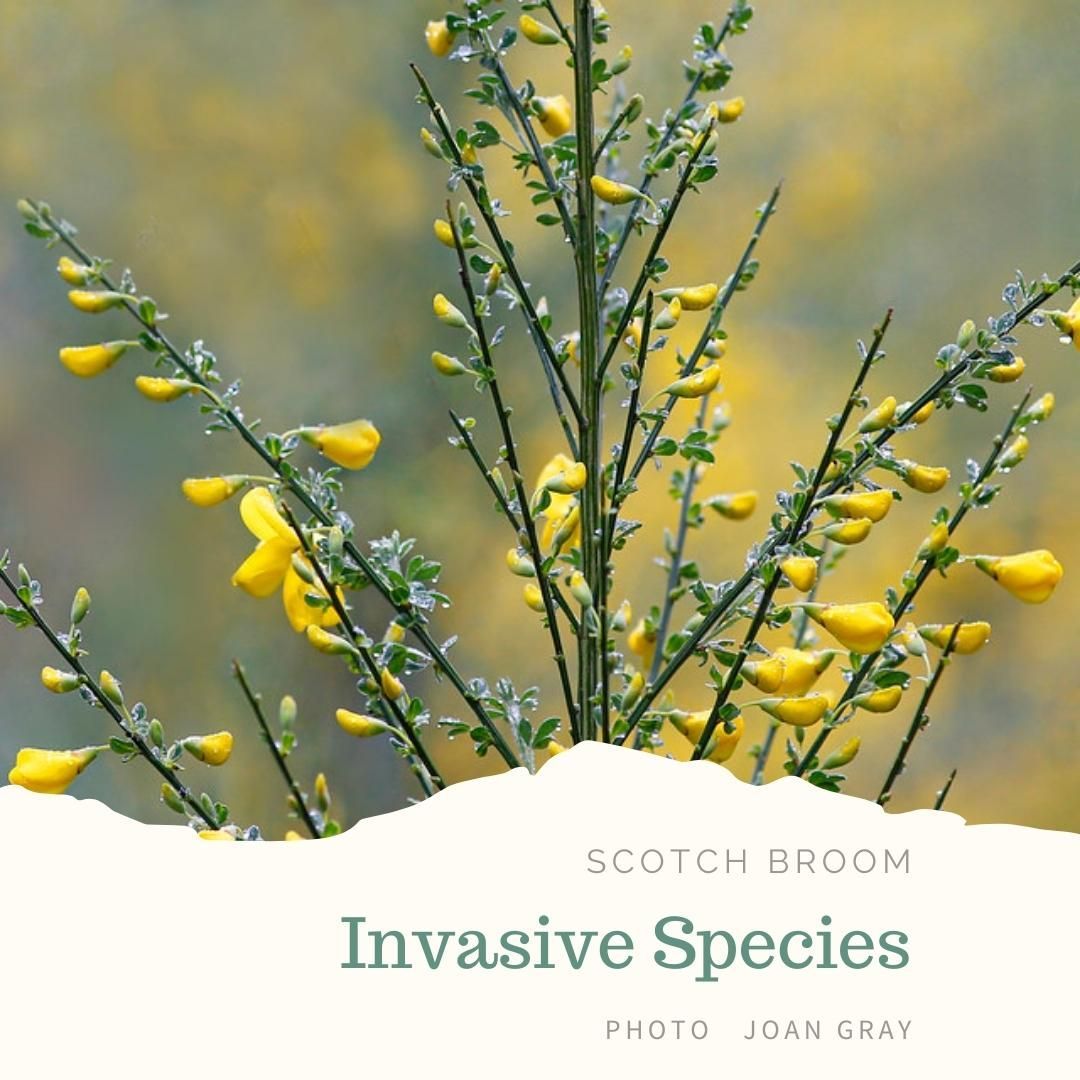

Don’t let the beautiful yellow colour of its flowers fool you – this is not a species you want in your garden! Scotch broom is a forceful invasive species that can increase the risk of wildfire and crowd out native plants that local animals rely on. If you find Scotch broom in your area, we have one piece of advice: Take. It. Out!

This invasive species is especially persistent due to its vigorous root system that has been known to grow and break through concrete and asphalt! Originally introduced as an ornamental species, it now wreaks havoc on local environments by spreading quickly and creating dense thickets that degrade wildlife habitat and reduce plant biodiversity. Your time is up, Japanese Knotweed — it’s time to take it out!

Did you know Giant Hogweed is a member of the carrot family? This giant invasive species can grow up to 3m tall! It contains a phototoxic sap that, if exposed to light, causes severe burns to our skin. For this reason, it can be dangerous to remove and should not be burned or composted. Instead, it is recommended to pull when it is young and small and then store in a sealed black garbage bag until it has completely dried out and the seeds are no longer viable. Giant Hogweed, it’s time to go!

This invasive species enjoys taking over areas with moist soils, including river and stream banks. Although beautiful, it produces a lot of plant nectar that attracts bees and other pollinators away from neighbouring native plant species. It can grow up to 2 meters tall and when seed pods are ripe, can explode and spread seeds up to 7 meters! It is easily hand pulled and bagged for removal, and it’s best done before the seed pods are ready to explode.

You’ve probably snacked on Himalayan Blackberries on a hot summer day, maybe you’ve even baked them in a pie, but did you know they’re extremely invasive to our area? Despite their delicious berries, they are known to crowd out low-growing native vegetation and create dense thickets that limit the movement of local animals. Part of our restoration work involves removing this prickly species from disturbed sites.